From Coercion to Collapse: How BC’s Vaccination Policy Lost Its Frontline Clinicians

Part 2 – When Doctors Opt Out: The Canary in the Coal Mine

In Part 1, we saw how the vaccinate‑or‑mask policy created the appearance of consensus. High coverage numbers sat on top of stigma and pressure, not durable trust.

In Part 2, we turn to the people whose behavior should tell us most about the program’s real credibility: physicians, nurses, and management.

Physicians: The Early Vote of No Confidence

Official messaging suggested physicians were among the strongest supporters of influenza vaccination—scientifically literate, aligned with public health leadership, and leading by example.

BC CDC’s influenza immunization occupational data in acute care1 tell a different story.

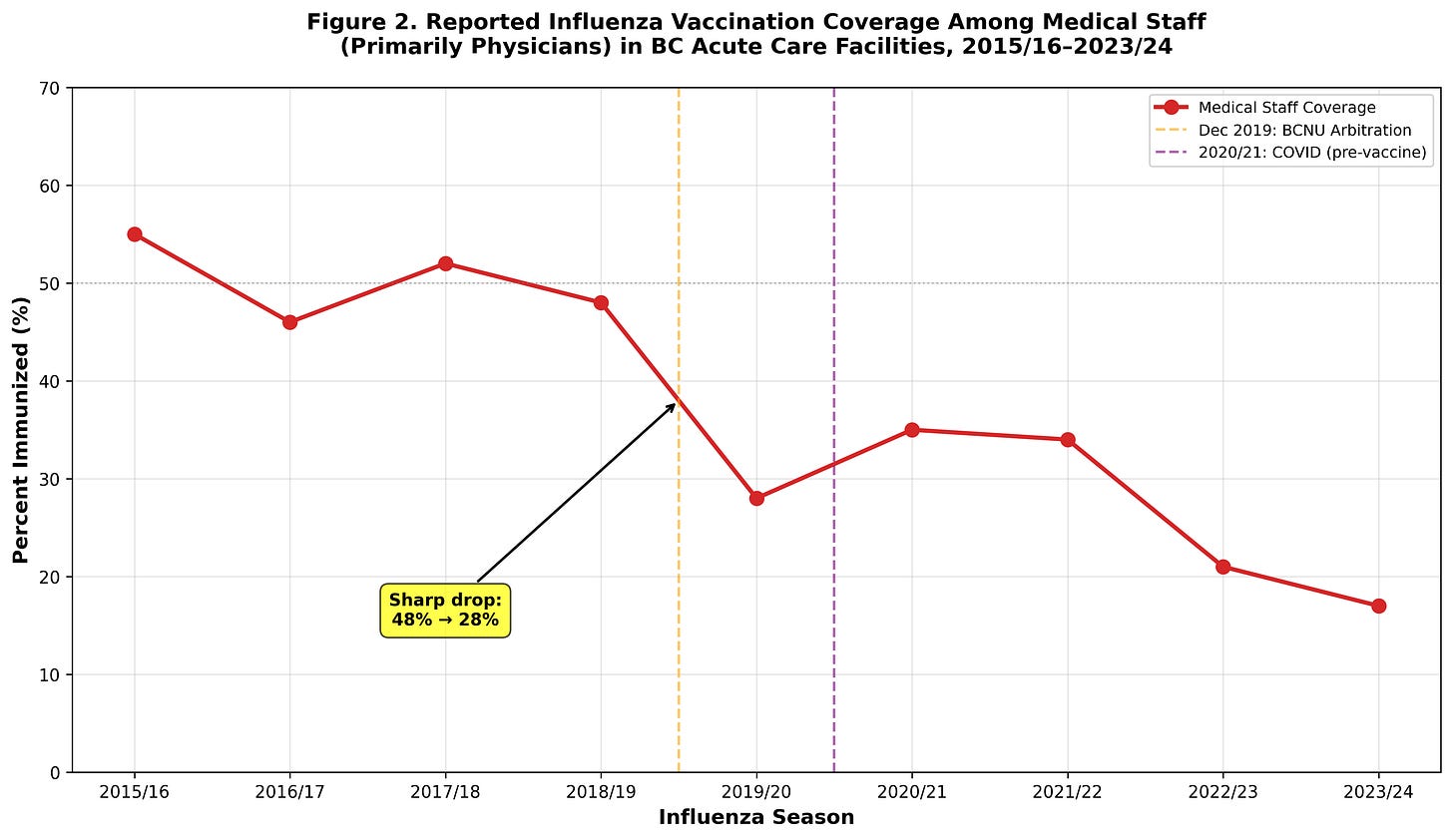

For medical staff (primarily physicians):

2015/16–2018/19: coverage hovers around 50–55%.

2018/19: about 48% report vaccination.

2019/20 (pre‑COVID vaccines): coverage drops to roughly 28%.

2020/21 (COVID, no COVID‑19 vaccines yet): 35%.

2023/24: coverage falls further to 17%.

Figure 2 tracks this decline. Physician uptake never reaches the lofty levels implied by provincial averages. Instead, it drifts around 50%, then collapses between 2018/19 and 2019/20, well before COVID vaccines and before the peak of “misinformation” rhetoric.

We do not have survey data on why individual physicians opted out. Reasons likely vary. But the size and timing of the drop make it hard to blame random noise, “pandemic fatigue,” or social media “disinformation” alone.

At minimum, physicians were far less enthusiastic about the flu shot than public health leadership implied. At the stronger end, their move from ~50% to 28%, and later 17%, looks like a vote of no confidence in the influenza prevention policy’s real‑world benefit.

Quantifying the Judgment Gap: Doctors, Nurses, Management

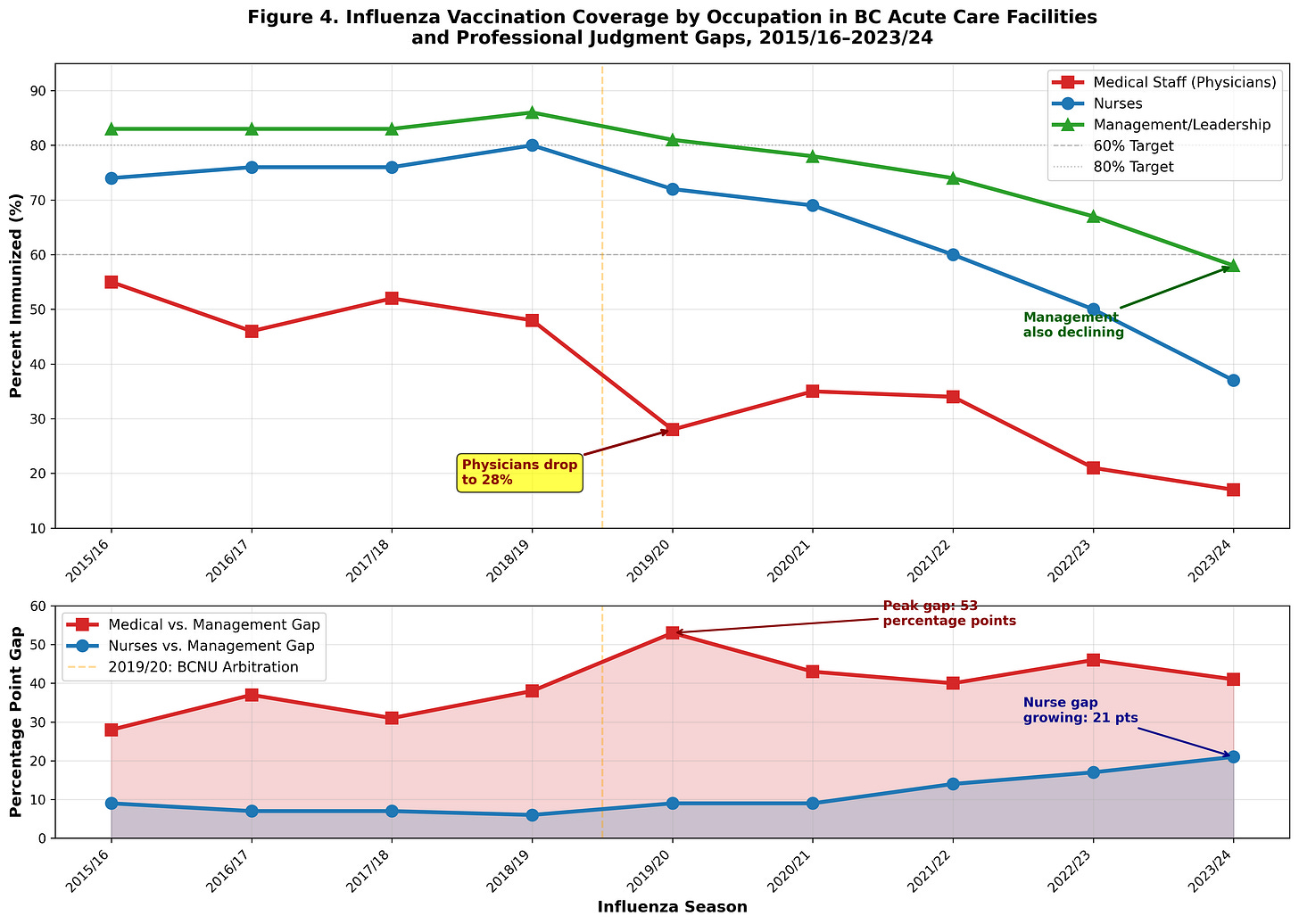

Occupational breakdowns sharpen the picture. Instead of asking vaguely whether “staff” support the policy, we can see how different groups diverge.

Figure 4 shows influenza vaccination coverage for:

Medical staff (physicians)

Nurses

Management/leadership

from 2015/16 to 2023/24. The top panel shows the coverage rates. The bottom panel converts those differences into “judgment gaps”: percentage‑point gaps between each clinical group and management.

Three patterns stand out:

Physicians’ gap with management is large and persistent.

2015/16: 55% vs. 83% → 28‑point gap

2018/19: 48% vs. 86% → 38‑point gap

2019/20: 28% vs. 81% → 53‑point gap (the peak)

That 2019/20 peak is crucial: at a time when management was still above 80%, physicians had already dropped to barely a quarter.

The gap narrows later only because management starts to fall.

2023/24: physicians at 17%, management at 58% → 41‑point gap

The reason isn’t a physician rebound; it’s that management is now quietly losing confidence as well, sliding from 81% (2019/20) and 86% (2018/19) down to 58%. In other words, the physician‑management gap narrows not because their views converge upward, but because both lines are converging downward—physicians leading the descent.

Nurses’ gap starts small but grows steadily.

2015/16: nurses 74% vs. management 83% → 9 points

2018/19: 80% vs. 86% → 6 points

2019/20: 72% vs. 81% → 9 points again

2023/24: 37% vs. 58% → 21 points

The turning point for nurses aligns with the BCNU arbitration decision that removed the vaccinate‑or‑mask requirement.2 While that rule was in place, nurses largely moved with management. Once it disappeared, their coverage started sliding: 80% → 72% → 60% → 50% → 37%.

In other words, coercion, not conviction, kept nurse coverage high.

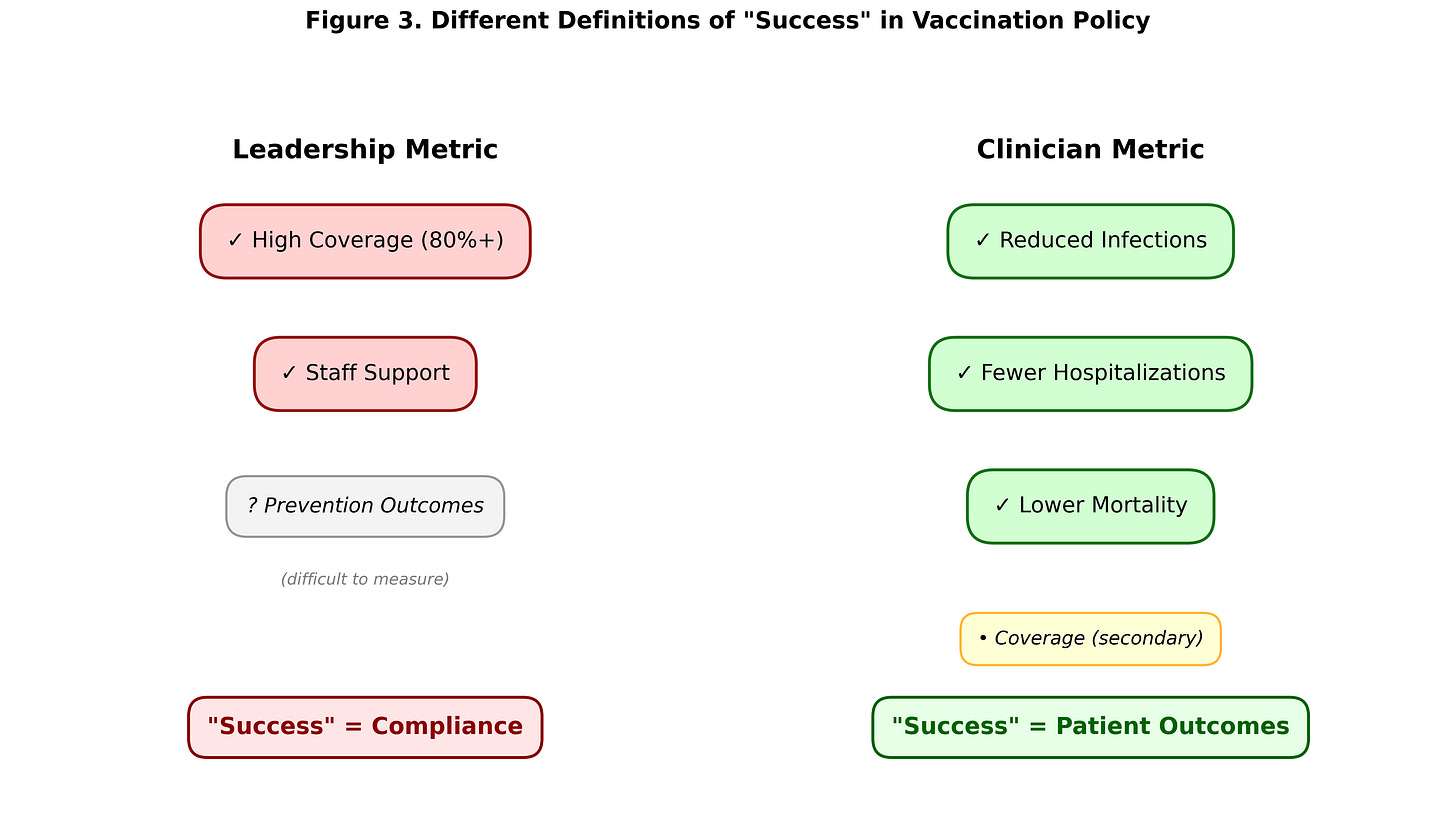

When “Success” Stops Meaning Prevention

Everything so far might be dismissed as a misunderstanding—if leadership had been straightforward about what they were doing. They were not.

In their January 2020 evaluation of the policy, Bonnie Henry, Provincial Health Officer of BC, and co-authors wrote:3

“The success of these types of policies in preventing influenza is difficult to measure. In the absence of a measure of influenza prevention, success has been described as high vaccine coverage and staff support for the policy. The vaccinate-or mask policy implemented in Horizon Health Network in New Brunswick has been very successful in achieving anecdotally reported compliance by HCW of 100%.”

This is not just an academic nuance. It crystallizes the core problem:

Prevention—the stated goal—is acknowledged to be hard to measure.

In practice, coverage and staff support stand in as the definition of “success.”

A policy can be called “very successful” based on anecdotal reports of 100% compliance, not on demonstrated reductions in disease.

For frontline clinicians, trained to think in terms of patient outcomes and clinical benefit, this feels upside‑down.

It looks less like a prevention program and more like a compliance program with a prevention story wrapped around it.

It signals that the system cares more about visible compliance than demonstrable benefit. It also explains why so many physicians and nurses walked away as soon as they could do so without wearing a mask or risking discipline.

Their judgement was simple:

If you can’t show that this meaningfully reduces harm, and if you treat my compliance as the main outcome, then you have lost the moral authority to insist.

Figure 3 illustrates this divergence. Public health leadership defines success primarily in terms of high coverage and staff support, with prevention outcomes acknowledged as “difficult to measure.” Frontline clinicians, by contrast, prioritize measurable patient outcomes—fewer infections, hospitalizations, and deaths—with coverage serving only as a secondary indicator.

This is the core of the credibility problem:

Public messaging frames the policy as a science-based tool to protect vulnerable patients.

The January 2020 academic write-up (Bonnie Henry and co-authors) concedes that we don’t actually have good measures of prevention—and then substitutes compliance itself as the primary success metric.

You don’t need to be “anti-vax” to see why that feels backward. If, by the leadership’s own account, the thing being optimized is coverage and buy-in, not demonstrated reductions in harm, many clinicians will reasonably conclude that the real priority is obedience to policy, not outcomes at the bedside.

When communicable-disease “prevention” is defined in practice as “high coverage and staff support,” with no robust measure of clinical benefit, it is hard for frontline clinicians to avoid the conclusion that prevention has become, at least in part, a pretext for enforcing compliance rather than the other way around.

Against that backdrop, the later collapse in uptake among physicians and nurses looks less like random resistance and more like a withholding of consent from a system that stopped measuring success in the same terms they use: did this actually help my patients?

Part 3 will show how that withdrawal unfolded at the system level: how the provincial numbers fell off a cliff, how transparency broke down, and what all this implies for COVID‑19 vaccine policy.

Data Notes and Limitations

Source: BC CDC reports on influenza vaccination coverage among acute-care staff and health-care workers in BC facilities.

Definitions: “Acute-care staff” and “medical staff” follow BC CDC occupational categories.

Measurement: Coverage is based on reported counts of vaccinated staff over each respiratory season.

Limits: Data do not capture individual motives or every possible confounder (e.g., changes in staff mix or reporting). They do clearly show large, sustained shifts in reported uptake, especially among physicians and nurses.

Acknowledging these limits doesn’t weaken the core finding; it underlines it. Even under conservative assumptions, the pattern of declining uptake among frontline clinicians is too large and consistent to reconcile with claims of stable, enthusiastic consensus.

Be somewhat dubious of the data presented here.

Unlike the Covid vaxxes which were strictly and carefully controlled by government operatives, flu shots were widely dispersed. So reported uptake may not have exactly matched actual injections. "I gave at the office" was quite possible with the flu shots, but closely policed with the Covid injections.

Again! Brilliant topic of analysis!

Honestly, I used to be a LOVER of Canada's Healthcare.

But I now realise it's only the front door entrance that's public.

All decision-making and policy lobbying controls all policy, and that policy REMAINS private profits.

All "covid" policy was geared for Big Pharma profits, nothing else.

Sure would be nice if you could interview one of those 72% of doctors who declined the shot in 2019